Not technically a place, the Port and Docks, now simply known as Dublin Port, was originally established in 1707 as the Ballast Board and has been headquartered at various places along the Liffey according to the shoreline of the river’s mouth as it opens into the Irish Sea. The earliest ports in Dublin were associated with the Viking establishment centered at Dublin Castle, and the ports have moved continually downstream as a result of the management of the river’s banks with the building of the South Wall in 1715 and the Bull Wall on the north shore in 1842. By the time James Joyce referenced the Port and Docks as the employer of Gabriel’s father T.J. Conroy, they were an organization whose main industry and activity happened along the North Wall of the Liffey at the eastern edges of Dublin:

“They both kissed Gabriel frankly. He was their favourite nephew, the son of their dead elder sister, Ellen, who had married T.J. Conroy of the Port and Docks” (179).

We never learn what T.J. Conroy did for the Port and Docks, “which was responsible for both the port of Dublin and for all the lighthouses around the Irish coast.” An 1883 Letts, Son, and Co. map shows the various yards, works, and buildings housed between the Custom House in the west and the mouth of the Liffey in the east.

One of the Port and Docks’s preeminent figures was Bindon Blood Stoney, who began work at the Ballast Board (as it was then called until it was renamed in 1869) in 1856 as assistant to the chief engineer. He advanced quickly, and by 1862 he replaced his successor as chief engineer and began implementing a method he had been developing to convert half of the city’s quays to deepwater quays. According to the Dictionary of Irish Architects (linked above),

“Stoney described his method in a paper, ‘On the construction of harbour and marine works with artificial blocks of large size’, delivered to the Institution of Civil Engineers in London in 1874, which gained him the Institution’s Telford Medal and Premium for that year. The method was used for the extension of the North Quay and the construction of the Alexandra Basin and for the foundations of the North Bull lighthouse. Stoney also introduced a more efficient system for dredging the shipping channel within the harbour, designing hopper barges of unprecedented capacity to carry the dredgings out to sea. Other works which he designed included the rebuilding of Essex and Carlisle Bridges and the construction of the Beresford (or Butt) Swing Bridge. He also was reponsible for introducing a graduated pensions scheme for his workers.”

When Carlisle Bridge was rebuilt in 1876, it was renamed O’Connell Bridge, a bridge Gabriel and Gretta cross later in “The Dead” on their way to the Gresham Hotel after his aunts’ party in Usher Island, one of the westernmost quays along the Liffey. According to Dublin: The City within the Grand and Royal Canals and the Circular Road with the Phoenix Park, “[Stoney] virtually trebled the width of the bridge to match that of O’Connell Street, and levelled the approaches by substituting broad elliptical arches for the original semicircular spans” (694).

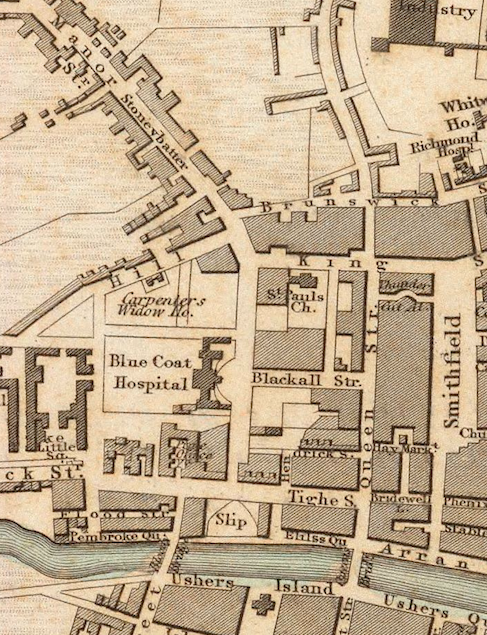

At the very least, because of Stoney, we know T.J. Conroy would probably have a satisfactory pension from his time at the Port and Docks, and Gabriel and Gretta’s crossing of the Liffey would be smooth and, as the text verifies, uneventful other than the cab occupants’ observation of Daniel O’Connell’s statue as they emerge on the north side of the Liffey. It’s perhaps also worth noting that early in the same story, we learn that Gabriel’s aunts, before moving into the house where the story is mostly set in Usher’s Island, lived with their brother Pat in “Stoney Batter” (both pictured below), an area that is labelled Stoneybatter on both an 1836 and 1883 map. Since the name appears on an 1836 map of Dublin, though, it’s not likely that the area was named after Bindon Blood Stoney. Nevertheless, the combination of the story’s references to several quays, Stoney Batter, O’Connell Bridge, and the Port and Docks makes it impossible to not encounter Bindon Blood Stoney while researching these places.